The data will save us — Or at least, that’s the hope of Wharton professor Duncan Watts, whose new initiative, the Penn Media Accountability Project, aims to expose bias in journalism by building a huge database of news for researchers and journalism watchdogs to analyze. What’s at stake? Only the future of the free press and perhaps democracy itself.

The data will save us — Or at least, that’s the hope of Wharton professor Duncan Watts, whose new initiative, the Penn Media Accountability Project, aims to expose bias in journalism by building a huge database of news for researchers and journalism watchdogs to analyze. What’s at stake? Only the future of the free press and perhaps democracy itself.

Professor Duncan Watts (Photograph by Jill Greenberg)

Duncan Watts is sitting in his home office, surrounded by spare walls, a skylight, a potted plant, and squealing children in the next room. He’s talking about what it would be like to be a God — not at all in a megalomaniacal sense, but for research purposes. “Let’s imagine you were a very naive God,” Watts is saying. “You can consume any amount of information, but you believe everything you read. What would you think? What would your impression of the world be?”

This isn’t a question purely in the realm of make-believe. It forms the basis of Watts’s work with the Penn Media Accountability Project, his research initiative at Penn’s Computational Social Science Lab in partnership with Wharton that’s seeking to better understand bias in the media — by thinking both about which stories publications choose to cover and how they frame them — and its impact on the rest of us. If everything goes Watts’s way, PennMAP, as it’s known, could end up being a kind of self-appointed ombudsman for the entire fourth estate — something Watts believes is long overdue. The mainstream media, he says, “haven’t received so much focus in the research community, because everybody in the ‘fake news’ research world treats them as if they only ever tell the truth.” He isn’t so sure. “I think it’s important to hold them accountable as well,” he says. “They’re very big on holding other people accountable but much less enthusiastic about being held to account themselves.”

It can be a slightly risky proposition these days to criticize the mainstream media — democracy dies in darkness, remember? — but Watts isn’t speaking out as a crank. (Although he is arguably cranky: When he mentions getting the New York Times in print each morning, he can’t resist adding that he finds it “equal parts indispensable and infuriating.”) His perspective mostly comes from the belief that the media is an essential component of civil society, which is all the more reason to analyze and understand its impact.

So now you can understand why Watts is pontificating about what it would be like to be a god, or at least to have a “god’s-eye view” of the information ecosystem. Unfortunately for Watts — a Penn Integrates Knowledge professor with appointments in Wharton, the Annenberg School, and the School of Engineering and Applied Science — he’s a mere corporeal being, albeit one with a few more college professorships than most of us.

He does have the next best thing, though: data — many, many terabytes’ worth. Every single show and advertisement broadcast on television going back to 2012? Watts has it, courtesy of TVEyes, a media monitoring firm. He’s got a similar set of data for news articles published on the web — everything from so-called “pink slime” publications trafficking in disinformation and lies to the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. He’s got individual-level television-and-web-viewing stats from Nielsen and data on over 10 million YouTube videos. He’s got every single Facebook link that was publicly shared more than 100 times in recent years.

It’s a “staggering” amount of data, he says, “way more than we could ever use ourselves.” Which is exactly why Watts is hoping to turn PennMAP into a resource full of wide-ranging, constantly regenerating data — a kind of media telescope that will allow academics everywhere to systematically examine what news publishers churn out over any given period. “We’ve spent years and lots of money building this data infrastructure that nobody else would want to build, because it takes years and lots of money,” Watts says. Once it’s completed, though, he adds, “The marginal cost of the next research project becomes very low.”

PennMAP is nothing if not timely. Conspiracy theories and partisan news are plentiful and popular in social media’s algorithmic marketplace of ideas. On any given day, the most-shared articles on Facebook are more likely to come from Dan Bongino or Occupy Democrats than major newspapers or NPR. A recent Gallup poll found that just 36 percent of Americans have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in mass media such as newspapers, TV and radio, down from 53 percent in 1997. The inter-party breakdown is stark: 68 percent of Democrats say they still trust mass media, compared to just 11 percent of Republicans.

“We have to be able to explain to journalists, ‘Here’s what we see you’re doing, and here’s what effect we think it’s having on the world,’” says Watts.

“We have to be able to explain to journalists, ‘Here’s what we see you’re doing, and here’s what effect we think it’s having on the world,’” says Watts.

By creating a data set that contains, ideally, almost everything that’s published or broadcast on a given day, Watts is hoping to open entire new avenues of inquiry. He wants to investigate mainstream publications that may not be topping Facebook shares but still reach millions of readers and publish huge numbers of articles. He wants to investigate radio and broadcasting figures like hyper-partisan Bongino and mega-popular Joe Rogan. He wants to publish public-facing dashboards on the PennMAP website that will demonstrate his findings in easy-to-understand visuals. How much time do people spend consuming different news sources? How biased is one publisher compared to another? Is fake news actually worse than subtly biased mainstream media? How does biased information affect a person’s beliefs?

This is what he’s after. First, though, he’s got to finish building the data set. “It’s just taken,” he says, “an ungodly amount of time.”

Tracking Watts’s career is like putting together an evidence board in a detective show: mazes of string connecting in unusual and unexpected directions. He grew up in Toowoomba, a town not far from Brisbane, on the east coast of Australia that’s mostly known for its farming. (His father, a farmer who later got involved in local government, had studied plant physiology abroad.) “As implausible as it might have seemed to my peers and even my teachers,” Watts says, “I kind of always had this idea in my head that when I grew up, I would go overseas and study, because that’s what my parents had done.”

Watts got an undergrad degree in physics from the Australian Defence Force Academy, served in the Royal Australian Navy, then earned a PhD in engineering from Cornell in the late ’90s. From early on, he had a knack for working on emerging fields. “I wrote my dissertation on what would eventually be called ‘network science,’” he says. “It wasn’t called ‘network science’ at the time because it didn’t really exist.” A few years later, more change came calling. “I switched fields and became a sociologist,” Watts says nonchalantly, as if that’s something one decides over lunch. He did three one-year postdocs and became a professor at Columbia at 29 years old. Watts’s first academic paper — which described what would become known as “small-world networks,” or the fact that most people have only a few degrees of separation from each other — was published in Nature and became a foundational text in the new field of network science. It has since been cited nearly 50,000 times.

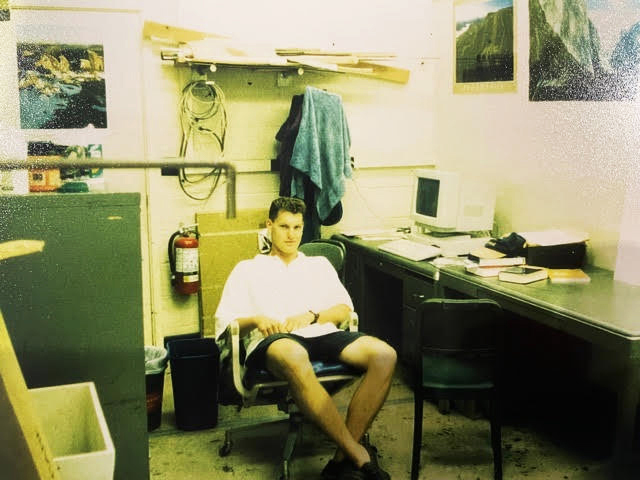

Portrait of the Professor as a Young Man: Watts in the Cornell office where he wrote his dissertation on small-world networks, circa 1996 (Photo: Alex James)

By the early 2000s, Watts was getting restless again. He’d been paying attention to the emergence of social media, message boards, and dating websites on the early internet. Here was a new set of networks, only now they were coming from computers. “I could see back then that the social sciences were going to become computational. There was this sort of revolution coming, and I wanted to be part of it,” he says. He went to Yahoo, where he worked on computational social science — yet another burgeoning discipline that “hadn’t really been invented” yet. After a stint at Microsoft, Watts arrived at Penn in 2019. “I finally got a job that reflected what I was trying to do all along,” Watts says, “which is work between disciplines.”

Watts’s scattershot career would seemingly make him the ideal person to put together something like PennMAP, with its mix of computer science (natural language processing and machine learning) and social science (designing ways to measure bias and its impact on behavior). He got a head start as a researcher at Microsoft in 2016 when he created Project Ratio, a precursor to PennMAP that sought to understand the same problems of bias. When Watts moved to Penn, he brought Project Ratio with him and changed the name to PennMAP last year.

Around the same time that Watts took the job at Penn, Richard Mack W89, CEO of the Mack Real Estate Group, decided he wanted to make a gift to support emerging research at Wharton. The question was: What research? “I was really thinking about what was bothering me about the world,” Mack says. His mind went back to the famous Ben Franklin quote that now makes an appearance on the front page of the PennMAP website: “Half the truth is often a great lie.” (The quote can also be found, carved in granite, along Locust Walk.) Mack realized what was bothering him was this: Partisanship seemed to have gotten so bad that conversation between opposing sides felt fruitless. “If we can’t agree on what the truth is or what the facts are,” Mack says, “how can we have a civil conversation around anything?”

Wharton was already doing some work in this department. There’s the Penn Wharton Budget Model, which uses high-tech data modeling to perform non-partisan analysis of legislation and its impact on the economy. There’s FactCheck.org, part of the Annenberg School, which has the full-time job (and then some) of cataloging and correcting lies from politicians. But both those groups were already well established. PennMAP — with its intensive database-building that required not just time but considerable financial resources — presented a different sort of challenge.

Watts and Mack first met in March 2020 at Mack’s offices in New York City. “We started talking about the fact that it was really hard to agree on what the truth is,” Mack says. “Duncan argued to me that there’s probably no absolute truth. But we can detect bias.” Mack, with his own concerns about how the media seemed to impede discourse, was intrigued. But then a pandemic happened, and as a real estate CEO, Mack suddenly had some pressing business concerns. Watts figured his promising meeting with Mack was going to end up an unfortunate missed connection.

Change Agent: Concerns about partisan influences on the media inspired Mack Real Estate Group CEO Richard Mack W89 to support PennMAP.

Then, in 2021, Mack reached back out. He still wanted to support PennMAP, having become convinced that “this was a place technology could really help us as a society.” The two got to talking once more. Watts came away impressed that Mack understood this wasn’t a snap-your-fingers-and-save-the-day kind of project. “When you go and talk to funders about needing to build infrastructure to help people do better research, their eyes just glaze over,” Watts says. Mack’s eyes did no such thing: “He was totally open to the idea that there’s this big, complicated machine that you have to build in order to do something that sounds simple, which is: Tell me what’s true.”

If you knew nothing about Watts and PennMAP, you might think the project would be consumed with vanquishing the typical media-bias bogeyman: fake news. Not so, says Watts: “The reason I don’t talk about outright false news so much is because there’s not nearly as much of it as everyone thinks.” In 2017, writing in the Columbia Journalism Review with his Microsoft colleague, David Rothschild, Watts noted that during the period of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election — the quintessential fake-news case study — bogus posts reached 126 million people on Facebook. That sounds like a huge number, but over the same period, people on Facebook saw a total of 11 trillion posts, meaning that for every fake news post, there were 87,000 authentic ones. In another paper, from 2020, Watts noted that fake news constituted less than one percent of news consumption across all age groups, on average. To Watts, the fake-news narrative is “another example of the mainstream media telling you what they want you to think.”

Watts is thinking instead about whether there’s bias in all those other posts — the real ones. In six days before the 2016 election, according to one of Watts’s analyses, the New York Times ran as many cover stories on Hillary Clinton’s emails as it did on policy in the entire two months prior to the election. “Clearly, this is a choice,” Watts says. “They didn’t have to write about it every day, and they could have written about other things instead.” Watts emphasizes that the mere act of selecting what gets covered as the news — even if the stories themselves are presented neutrally — has its own bias. And that’s assuming news outlets frame their stories neutrally, which anyone who has spent a minute watching cable knows isn’t always the case.

“Duncan argued to me that there’s probably no absolute truth,” says Richard Mack W89. “But we can detect bias.”

“Duncan argued to me that there’s probably no absolute truth,” says Richard Mack W89. “But we can detect bias.”

Another of Watts’s recent studies seeks to understand this phenomenon of exposing people to seemingly neutral but in fact biased information. In the study, Watts and his co-authors asked participants to bet on whether a college dropout or a college graduate would be more likely to launch a billion-dollar “unicorn” startup. Anecdotal evidence of success abounds on both sides, so before asking the participants to place bets, the researchers cherry-picked the data. One group was given examples of successful dropout founders, one group got examples of successful college-grad founders, and one group received nothing at all. Then the researchers told everyone what they’d done, emphasizing that despite the information the participants had just received, there were plenty of examples to the contrary. The disclosures were so explicit that Watts recalls worrying they’d gone too far, to the point where they had torpedoed their own experiment. Surely no one would be swayed by such obviously biased data, right?

Wrong. When they showed the participants two other startups — one founded by a college grad and one by a dropout — and asked which they would bet on to become a unicorn, the group that had seen college-grad examples bet on the grad founder 87 percent of the time. When the group that had been shown successful dropouts was asked to make the same choice, just 32 percent bet on the college grad. (The participants who had read nothing at all, meanwhile, bet on the college grad 47 percent of the time.) For Watts, the result produced a profound — if startling — realization. “You do not need to lie to people to mislead them,” he says. Giving people data that is factually correct but is carefully selected to support the conclusion you want them to reach is enough. Who needs fake news when you can use the real thing instead?

Watts isn’t the only Wharton researcher coming up with troubling findings about bias and media. Shiri Melumad, an assistant professor of marketing, has been examining the other end of the media ecosystem: what happens once an article is shared. In one recent study, Melumad had participants read a series of made-up news articles and asked them to summarize the stories to a second group — effectively re-creating a social media chain of sharing and commenting on an article.

Negative-Bias Effect: Marketing professor Shiri Melumad’s research serves as a complement to PennMAP, looking at what happens once an article is shared.

The findings, Melumad says, were “scary.” Every time the participants retold the story, they increasingly “injected their personal opinions” into the subject, and they also became more negative in their summaries. Melumad found that it was nearly impossible to halt this dynamic — even a story about a boy overcoming a handicap to become a champion swimmer produced the negative-bias effect with each retelling.

This has some not-so-great implications for the world and PennMAP alike. If our default mode of sharing is to add negativity in our retellings, does it even matter if the media becomes less biased? Isn’t it inevitable that we just end up in an increasingly negative whirlpool of posting?

That isn’t stopping Watts from trying to find out more, though. He’s hopeful the database will be fully constructed within the next year, at which point PennMAP can pivot from the minutiae of coding and construction to running experiments that might answer some of the big-picture questions both he and Mack have in mind. “Until we’ve managed to build the algorithm, all of the ambitious goals are a lot of noise,” Mack says, noting that he hopes others will also join the cause. “For PennMAP to reach its potential, we encourage engagement and involvement from the Wharton alumni community.”

Watts isn’t naive enough to believe that PennMAP will reach everyone. “If you’re an Alex Jones adherent, you’re probably not that interested in what the University of Pennsylvania has to say,” he admits. But he’s hopeful mainstream media consumers and the editors at such publications will be open to some feedback. “We have to be able to explain to them, ‘Here’s what we see you’re doing, and here’s what effect we think it’s having on the world,’” Watts says. (Whether journalists will be receptive to outsiders telling them what they’re doing wrong remains an open question.) At the end of the day, as Mack points out, “Unless this is big, recognizable, and something that people have faith in, having built a great algorithm is not going to do us much good.”

PennMAP’s own bias sensors would almost certainly be set off if Watts and Mack tried to suggest success is a sure thing. In fact, both take pains to point out it might not be. “I don’t know if we can do it,” Watts says at one point. Mack likewise concedes, “It may be that none of this” — fundamentally altering people’s behavior, inspiring a more civil, informed discourse from the dinner table all the way up to the halls of Congress — “is achievable. But it’s worth getting started.”

David Murrell C17 is a senior staff writer at Philadelphia magazine.

Published as “The Data Will Save Us” in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Wharton Magazine.

%

Percentage of Americans who reported a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in U.S. media in 2021, according to Gallup